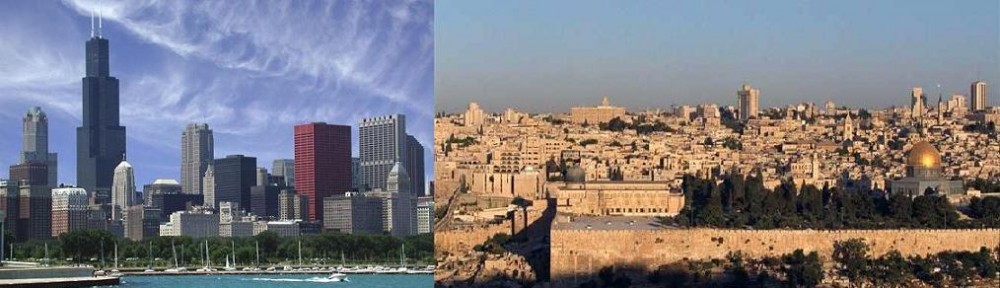

The thing about being in Israel — particularly Jerusalem — for holidays is the universality. Instead of a small pocket of observance in the larger world of non-Jews and non-observant Jews, virtually everyone here is at least generally on the same page. For Succos, this means succahs sprouting on virtually every marpeset (porch) and roof, piles of schach all over, and arba minim for sale everywhere.

In reality, I should’ve been more blown away by the phenomenon than I was. This is actually kind of a theme for our trip here. I think it has to do with feeling more like participants than spectators. A tourist oohs and aahs over the spectacle, but a resident is focused on how to get the succah up and where to get his arba minim.

My Dad joined us for the chag (holiday). He was a very good sport, and happily took on everything. If that had only meant full observance of Succos (and Shabbos) — eating and sleeping in the succah, abstaining from melacha (prohibited “work”) on the Yom Tov days and Shabbos, spending more time in services than he’s used to — it would have been impressive enough. But he also kept the second day of Yom Tov, when we were only keeping one day. That meant he had to make kiddush and havdalah for himself, and abstain from lots of activities he would’ve liked to do — such as take pictures — even as we and most of the city were treating the day as chol hamoed (or, for the last day, entirely chol (non-holy)).

Our own succah construction turned out to be more of an adventure than I’d anticipated. I was expecting it to be very easy. Our marpeset is really a chatzir (courtyard), with four stone walls. There’s a wooden frame bolted into the stone overhead, ready to be covered with schach. Not only that, but there were schach mats, rolled up in covers up on the bracket, ready to be rolled out. The only apparent complication was that the frame is pretty high up, about 15 feet, which would require a seriously high ladder. Locating such a ladder turned out to be a real issue. At best, I was able to borrow a ladder that would lean against the wall from which the frame could be reached if you stood on a high rung. But there was no hope of a v-shaped ladder high enough to reach the frame from the middle of the succah, greatly complicating the job of rolling out the mats.

After much hand-wringing, and some good advice, I decided on an American-style solution: hire somebody to do it for me. Moshe, a younger guy from the yeshiva was offering his services, so I called him up. I warned him about the difficult height, etc. But he’s an Israeli, and so was typically sanguine about the whole thing (national slogan: “ayn bayah” (“no problem”)). He came over, and decided that the easiest way to deal with the situation was to pull himself up onto the frame and work from up there. We were joined by my neighbor and also fellow Bircas learner, Kobe Eshet, who — as another Israeli — similarly saw no problem trusting the frame with Moshe’s weight. Because the mats were in terrible shape (water damaged, infested with bugs), we had to go buy some palm fronds, and Moshe put them up there.

As an aside, I find it really lame that, when they translate things like sports team names into Hebrew, for t-shirts and the like, they just transliterate them. For example, “Chicago Bulls” becomes “שיקגו בולס” instead of “שיקגו שוורים.” Perhaps the lamest example, though, is Spiderman (“ספיידרמן“), because translation would yield the utterly awesome “איש עכביש” (“eesh akaveesh“).

We had just been discussing איש עכביש that very evening (including my attempt to translate the Spiderman theme song into Hebrew). So, amazed by Moshe’s climbing dexterity and fearlessness, I promptly bestowed the name on him. The next morning, I told the boys about it:

“Guess who put up our schach!”

“Who, Abba?”

“איש עכביש!”

“Nooooooo, Abba — Spiderman’s not real!”

“Well, then, how do you explain how our schach got put up?”

[Stunned silence]

In the end, our succah felt a lot different from what I’m used to. It was wonderful and spacious but, with its relatively high ceiling and permanent walls, it didn’t have quite that same temporary (and shaky) feel that I get at home. There’s also the fact that there were no October Chicago winds howling against it. Due to the stone walls, to which no tape will stick, I strung up a clothesline around the sides, and we pinned up decorations. We added blinking lights this year, which the boys loved. I did find myself, as I was trying to sleep through the Times Square Effect, wishing that I’d set the timer to turn them off earlier. It was also a novelty to have it be too warm in the succah for comfortable sleeping. I hadn’t thought to set up a fan — a fact that had my neighbors tsk-tsking at me when I mentioned it.

Although I’d picked up my Dad’s and my lulavim and esrogim from someone at the yeshiva, I purposely held off getting them for the boys, because I wanted to go see the massive arba minim shuk (market) in Geula. Yitzi, my Dad, and I went there motzei Shabbos (Saturday night) to get the boys’ arba minim sets and to get decorations for our succah. The shuk was really cool, with so many people hawking their stuff, and men carefully inspecting the wares. It was full of a wide variety of Jews – chassidim, Yerushalmis, yeshiva bochrim (mostly from the nearby Mir yeshiva) – who were all having a good time. My Dad took some nice pics:

Every store in Geula/Meah Shearim seemed to have been converted to selling either arba minim or succah decorations.

By the way, I now understand why my friends who have lived in Israel bemoan every year the quality of the arba minim we get in Chicago. The quality here was so ridiculously good that I just kept laughing. The lulavim I got for the boys — chinuch (educational) sets that are only need to be barely kosher for a bracha — were easily better than those I’ve gotten for myself the last couple of years. And I’ve never seen ones in Chicago as nice as those I got for myself and my father this year.

By the way, I now understand why my friends who have lived in Israel bemoan every year the quality of the arba minim we get in Chicago. The quality here was so ridiculously good that I just kept laughing. The lulavim I got for the boys — chinuch (educational) sets that are only need to be barely kosher for a bracha — were easily better than those I’ve gotten for myself the last couple of years. And I’ve never seen ones in Chicago as nice as those I got for myself and my father this year.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about the entire holiday is that this did NOT turn into a sword fight.

This was Shalom’s first year with his own set. He’s actually still pretty young for it, but I wanted to surprise him with a special treat for our Succos in Israel. He was so delighted to have his very own lulav and esrog.

The thing that was just like home was that it actually rained — complete with lightning and thunder — the first night. Fortunately, it was well after we’d made kiddush and hamotze, so we got in our mitzvos of the evening. Locals said this was an extremely rare event, and no one could remember more than a sprinkling (and certainly not lightning & thunder) on Succos. The Talmud (mishna on Succah 28b) says that, if it rains (on the first night of Succos), forcing you to leave the succah, it is comparable to a servant who comes to fill the cup of his master, and the master pours it in his face. Nearly every year in Chicago, it either rains or threatens rain on Succos, so Rabbi Gross is perennially reminding us of the halacha in such a case, and mentioning that mishna. He always points out that it really only applies in Eretz Yisrael (Israel) — which was a great comfort… until this year.

Chol hamoed deserves its own posts — and I’ve already done a couple, including our trip to Nahariya and Bircas Cohanim. I’ll try to add something quick about the Western Wall Tunnels, which I highly recommend. And maybe our dinner at Entrecote, which I also highly recommend.

For all that we missed from home this Succos (including, probably more than anything, spending it with our cousins, the Presbergs), I already know that next year (assuming that we’re not all here — l’shanah haba’ah b’Yerushalayim habenuyah!) we’ll be feeling the loss of the magic of Succos in Yerushalayim.