After three months here, we’ve now had some exposure to the Israeli healthcare system – a bit more than we’d have liked, to be honest – and I thought I’d share our experience.

DISCLAIMER: I’m not trying to make any sweeping statements here about the Israeli or American healthcare systems. This is simply our own anecdotal experience, nothing more. In fact, not only do we have a very small sample size, but some of it may be particular to being in the Rova.

The exact structure and nature of the various healthcare entities here remains something of a mystery to us, so my summary may not be quite accurate. But this very uncertainty is also part of the authentic experience, so I’m not going to do a lot of “outside” research to clarify it for this post.

Everyone here pays the government for heath insurance, either via an income tax that ranges from 3-5%, or on a fee-per-person basis (if, like us, you are not employed here). This insurance entitles you to join one of the four HMOs that provide healthcare services, which HMOs apparently are paid by the government based on enrollment and other factors. Whether they are private companies, or quasi-public, or whatever, I don’t know. They vary somewhat, and you need to determine which services each provides (and doesn’t provide) and other factors (e.g., which is closest to you, or is best in your area) to decide which one to join, although you can switch between them. Meuchedet was strongly recommended to us. Also, it is one of just two that are here in the Rova. You can get supplementary insurance, which entitles you to additional services, though we won’t be eligible to buy it until we’ve been here 6 months. I understand that you can also get private healthcare, outside the ambit of the national plan and HMOs, but I don’t know much about its availability or cost.

In addition, for babies, there is the (government agency?) Tipat Chalav. It handles immunizations and basic baby development (height, weight, etc.).

Thank G-d, we haven’t had any serious problems, but we have had occasion to experience walk-in clinic assistance, treatment by specialists, attempted treatment by specialists, and a Tipat Chalav check-up. Here’s the good and not-so-good of it.

The Good

Most of the providers have been very helpful, concerned, and friendly. Over Rosh Hashanah, a nasty stomach bug made its way through the family. We each got it to varying degrees (except the baby, Baruch Hashem), but Debbie really got hit hard. Exacerbated by the fact that she was nursing, Debbie got dehydrated and needed to get some IV fluids the day after Yom Tov. She was able to make the short walk to the Meuchedet clinic (everywhere in the Rova is only a short walk), and they were lovely. There was no emergency-room-style wait – Debbie was promptly ushered in to the nurse’s office, made as comfortable as possible, and received immediate treatment. The nurse and doctor were both from South America, and kept switching between Hebrew, English, and Spanish amongst themselves. At one point, the doctor started singing “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina” (apropos of nothing, but charming nevertheless), and I had to tell Debbie later that he sung in Spanish. She was so out of it that she couldn’t keep track of the languages, recognizing only that she understood him. After Debbie was settled in and getting her fluids, I came back home to relieve the emergency babysitter, and the nurse would call to ask me to bring food and come get Debbie when she was ready. It was much more personal and personable than I’m sure we would’ve experienced at home.

Similarly, the dermatologist to whom Yitzi was referred for a plantar wart was a super-nice South African fellow with a terrific manner.

The other good thing is that this is all very cheap. We paid a guy here 1,000 NIS (a little over $250) to get us signed up for Meuchedet (i.e., to handle the red tape and get us signed up immediately), which included the first 6 months of coverage for the family. There are some copays, but they’re hardly worth mentioning. Seeing a specialist costs something like 20 NIS (roughly $5), and that covers all of your visits to that specialist for the fiscal quarter. For the family, specialist copays are capped at about 200 NIS (~$50) per quarter. Prescription drug copays are generally 14 NIS (~$3.50) (they can cost more if the drugs are especially expensive).

Of course, it is super-cheap for us because we don’t pay any income taxes here – healthcare or otherwise – and we’re even exempt from the V.A.T. Also, I have no idea whether the national healthcare income tax covers all of the costs or if it has to be supplemented with other tax revenues. The bottom line is that we’d certainly like to thank the Israeli taxpayers for subsidizing us!

The Not-So-Good

In order to see a specialist, you have to get a referral – and almost everything requires a specialist. When Yitzi got a painful plantar wart on his heel, Debbie made an appointment and took him to the local Meuchedet office. The doctor took a quick look, then apologetically said we needed to take him to a dermatologist, and filled out a referral. It was then up to us to find one. The closest one was outside of the Rova, roughly a 15-minute bus ride away. This has turned out to be, by far, the easiest specialist referral we’ve had to arrange.

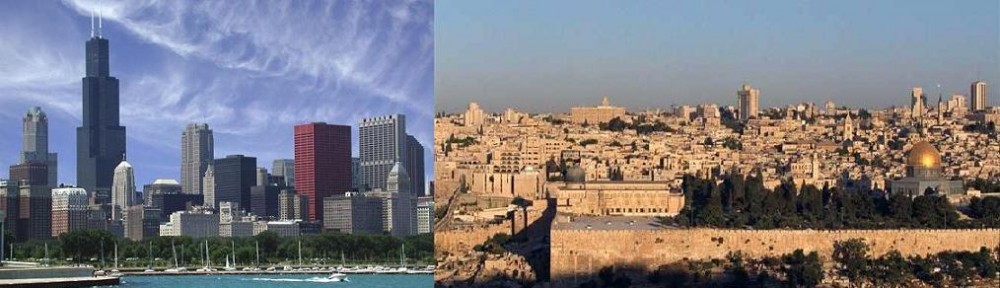

I have chronic problems with my ears, for which I see a hotshot specialist in Chicago. My ears need to be examined and cleaned every few months, at a minimum. In late September, when they started acting up, I called back to Chicago to get a referral. My doctor suggested his friend, the head of the ENT Dept. at Shaare Zedek hospital here in Jerusalem. I tried calling the doc’s office, which turned out to be its own challenge. His secretary was generally not there and – astonishingly – there was no voicemail. Eventually, I got ahold of her. She said I’d need to get a referral from Meuchedet, but she’d go ahead and schedule the appointment, but the first available was December 11. When I went to Meuchedet to get the referral, the doctor there told me that she could not refer me to a Shaare Tzedek doctor. I had to first see a Meuchedet ENT, who could then refer me if it was warranted. The soonest available Meuchedet ENT appointment was in three weeks, in Har Nof (a Jerusalem neighborhood about an hour away via public transportation). When I went to see her, she did not give me a referral, but treated me. I’ve decided not to make a stink just yet, unless we don’t see any improvement.

A couple of weeks ago, Baby Mordechai developed a nasty eye infection and possible blocked tear duct. Needless to say, he was going to need to see an eye specialist. Debbie got some recommendations and tried to make an appointment. She was told she couldn’t get an appointment yet, but should call back… in December.

Another thing about the healthcare infrastructure (which also seems to generally be true with many of the institutions here, like the phone companies, UPS, Egged, etc.) is that you’ll experience significantly different policies and procedures, depending on who you happen to talk to. For example, when Yitzi went in for his wart, he was told he had to go to a dermatologist. When I went in for my ear (to get a referral), I also pointed out that I, too, had a plantar wart that was bothering me. The doctor barely glanced at my foot, and prescribed a topical, with no further instructions or advice.

In fact, that doctor was the exception to the general rule of kind and friendly care (she was not the Evita-singing caretaker of Debbie’s visit). When I went in to see her, and asked if she spoke English, she gave me a brusque (and mildly hostile) “no.” But when I tried to describe my ear condition in my broken Hebrew, a miracle occurred, and she was suddenly able to speak very serviceable English. Even then, she was not too interested in the reasons I came to see her, wanting instead to talk about my diet and exercise regimen. To be sure, I certainly need to lose weight – in fact, I’ve been eating better and have been more active here, and have been losing weight – but I would have appreciated at least token attention to the things that brought me to her in the first place.

The In-Between

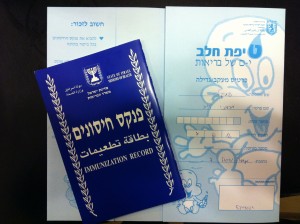

The most advanced recordkeeping method ever devised by mankind, according to Tipat Chalav.

Debbie’s Tipat Chalav visit with Mordechai didn’t live up to stories we’d heard of being overly hectoring. She reports that the nurse was very nice. But it is worth noting that Tipat Chalav provides a card on which they hand-write the baby’s growth data (measurements, weight, etc.), together with a handwritten vaccination record. Although all of this data is inputted into Tipat Chalav’s computer system, parents must keep these and bring them to each appointment, or else no baby well-care will be provided. The nurse explained to Debbie that this Israeli system is superior to the apparently confusing printout of Mordechai’s information from our doctor at home.

Like this:

Like Loading...